“Who Would Do This to Our Poor Little Babies?”

Dear Team Mosaica:

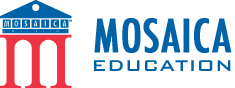

And so it goes. That aphorism from Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five rings in my ears as I stare at this death notice from today’s New York Times – perhaps the most horrifying listing in American history. It contains the names and ages of 20 six- and seven-year-old children and seven creative and dedicated educators, all killed within minutes of each other by a 20-year-old gunman in combat gear, armed with a semiautomatic rifle and two semiautomatic pistols that were loaded with ammunition designed for maximum damage:

The entire country has been staggered by Friday’s carnage at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in central Connecticut, the wails from inside the school echoing throughout the land, from President Obama’s emotional response to our own silent prayers to the tears of every parent who hugged his or her bewildered child over the weekend. We’re grief-stricken, angry, frustrated and frightened. But our most prevalent response is disbelief. We simply refuse to believe that this has happened again. We can’t explain this mindless slaughter to ourselves, and we wonder how to even talk about it with our children and students. How do we assure them that their classroom remains the sanctuary we have worked so hard to create? At the same time, how should we acknowledge the fundamental fears that events like the Sandy Hook killings trigger?

First, let’s keep things in perspective. The media have been quick to characterize school shootings as an “epidemic.” They’re not. They happen too often, to be sure, but they are still exceedingly rare. We, of course, need to be vigilant, but we should also not be quick to turn our schools into fortresses. We limit entry by visitors and have developed an explicit disaster plan, which includes strategies to lock down the school and pursue close ties with the local police in the event of an emergency. Those policies should be reviewed and renewed, but at the same time we should take care not to suggest to already vulnerable children that they are in immediate danger – or, worse, that they might be safer any place else.

We also have to be careful not to demonize the mentally ill or those suffering from some other disability. We don’t know enough about the perpetrator of this crime to diagnose him accurately – and perhaps we never will – but, once again, some talking heads have been quick with their assessments. If in fact the shooter had a developmental disorder or mental illness, that does not imply that others with that disorder or disability are potential murderers. If a student (or, for that matter, a misinformed adult) makes that kind of assertion, it may provide a teaching moment to counter the logical fallacy.

Ultimately, in our dealings with our children and students, we need to follow the recommendations of the medical Hippocratic oath: first, do no harm. Let’s listen before we talk. We need to understand what these children have heard. That puts the focus where it needs to be: on the child, not on the adult. We instinctually want to tell them what happened – and then drill them wildly on how to protect themselves. We want to promise them that it could “never happen here.” (Perhaps if we do, that will even convince us.) We may think our students are worried about what happened in Newtown because that’s all we’re thinking about. But they may actually know very little and may not be worried at all. It may be that the best thing we can do is to protect them from hearing about it.

If, however, your students are anxious, the strategy that’s commonly recommended is: “worried thought, brave thought.” The kids are taught to respond to their worried thoughts with brave thoughts. A worried thought might be, “A shooter might come to my school and there is nothing I can do about it,” to be countered with the brave thought, “School shootings are very rare, and lots of people are working to make sure nothing bad happens at my school.”

I have attached a PDF that includes detailed suggestions on helping children cope with trauma. In the meantime, let’s continue to keep the families of the Newtown victims in our prayers.

Michael J.Connelly Gene Eidelman DawnEidelman

Chief Executive Officer President Chief Education Officer